Welcome back to our series, twenty shades of “time is money”. Every Tuesday we’re breaking down findings from my research on social acceleration, marketing, and consumer culture.

This research helped me better understand my own relationship to time and consumption (and specifically, the felt need to constantly be busy and hurry through life and buy things as an antidote to this frenzy). Thank you for reading, and I hope there is a nugget of inspiration for you here too!

This week we’re covering a fourth way the cultural myth “time is money” became normalized in US consumer culture throughout the 20th century1:

“Fastness is desirable; an aspirational trait.” (This includes the equation of ‘fast’ with other aspirational traits reflected in US consumer culture such as ‘sexy’, ‘youthful’, ‘fashionable’, and ‘happy’.)

Above, the tempo of American life is portrayed by young, smiling, thrill-seeking car passengers. A fast tempo is youthful, and in America, youthfulness is to be desired. This thrill-seeking is not completely care-free however, as the advertisement promises safety to complement the discovery of new speeds. The technical drawing of the new tire technology indicates good engineering and high quality. In addition, the “proper” clothing choices of the young adults (dresses, driving gloves, sports jackets) still adheres to cultural norms, signifying the calculated risk of driving on the open road; pushing the boundaries… within reason. Acknowledging the desire for both speed and safety, the brand seems to say, “You live a fast, thrilling, and youthful life... our product can keep you going.”

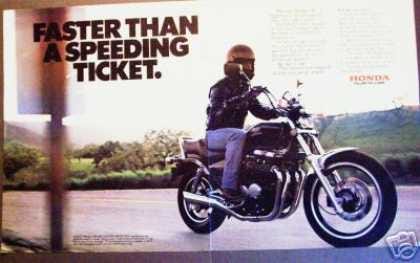

The above advertisement extends the cultural boundary of fastness, promising risk and a brief foray with consequence to provoke desire. “Faster than a speeding ticket,” the copy reads, “break past speed limits” because “a thrilling life is a fast life.”

The cultural myth “time is money” conveys fast is desirable…

But where do desires come from?

Desires often derive from normative beliefs; what we desire for ourselves is often a reflection of what others also desire. (This is the gist of mimetic theory, which I’ve written about in regard to influencing/deinfluencing.) And if we live in a culture that aspires for efficiency and productivity and fastness in nearly every aspect of life -- rushing through school drop offs and morning commutes and making meals and inbox zero and quick texts and running red lights and "no time for play" -- we may, without noticing, be swept up in the speed. By keeping a quick pace, we may not feel like we have the time to pause and reflect: “is this what I want?”

I don’t believe marketers create cultural norms (marketers didn’t create “time is money”), but savvy marketers do fan the flame of cultural norms that already exist — thus tapping into and perpetuating and profiting from collective desires.

The cultural myth “time is money” conveys fast is desirable…

Conversely, then, is ‘slow’ meant to convey something undesirable and not worthy of aspiration?

It’s interesting to see a 21st century reaction in the opposite direction. That, because fast has become a normalized ideal for the “masses”, slowness may actually be employed as a form of distinction.

Who gets to choose what’s desirable?

In the early 20th century, economists and political thinkers decided that generally, idle time would not be good for the public2. While technological advancements held potential to free up time for leisure activities, more leisure time for the masses would ensure a clash between classes and ideals. Instead, time spent working ensured two things: 1) preoccupation, and 2) a steady stream of money for consumer goods. (Actually, maybe 1 and 2 are the same.)

I’ve observed in recent years slow becoming a new object of desire — a way to portray style, happiness, and most importantly — insider knowledge, aka cultural capital.

Sociologist Pierre Bourdieu explains that people accumulate three types of capital to assert their standing in society: economic capital (money!), social capital (family and network ties), and cultural capital (education, access to knowledge).

Those with a high volume of cultural capital typically dictate what’s considered “good taste” (i.e., desirable) for everyone else - the theory of mimetic desire once again in play.

Bourdieu further argues that imposing a dominant form of desire can be considered an act of 'symbolic violence'. Those with less (economic, social, and cultural) capital typically (even if unknowingly) go along with standards set by the cultural elite, adopting them as an act of acculturation, but the sad truth is - by the time a majority has adopted to any given cultural trend, the powers that be will have moved onto something else entirely.

I’m all about slower living as a conduit to consuming more thoughtfully. All about it. In fact, I believe the two are intertwined and an important part of the path toward a more sustainable future. But I’ve noticed a distinction between the marketing of “slow” and the practice of “slow consumerism”. In my optimistic mind, the slow consumer is well intentioned and perhaps more caring of the social implications of hyperfast overconsumption. But if Bourdieu’s theory were to play out… slow as a desirable, and marketable, thing may become just another trend, a temporary thing to display.

Good thing it’s just a theory, and we have opportunity to create the future we’d like to see.

**By the way - two companies leaning into “slow” and doing it right: Slowdown Studio (online) and Slow Yourself Down (Hanalei, Hawaii and online). I’m sure there’s more - would love to hear any you’ve seen!

If you missed the tutorial on how I analyzed hundreds of vintage advertisements for their symbolic meanings, you can find that here!

The 20th century interwar period in the West was crucial in determining the tradeoff between leisure time and consumption. Enlightenment thinkers decided our fate based on a paradox: “For some, prosperity undermined work effort and created the anarchy of undisciplined time; for others, it multiplied need and produced a work-driven society based on ‘false needs’”. Ultimately, society began to view the combination of general affluence and extensive freedom from work as a moral problem, and thus the latter viewpoint won out. This led to the emergence of a mass consumer society in the US and Western Europe.

Have you heard of Monk Manual before? It's a really unique product rooted in the ideas of intention and careful, meticulous planning. Although based on the mystic life, it has mass appeal. Although these two things may not necessarily seem able to be conjoined (and of course, this is only one example), the appeal makes me think people are moving in a different direction. I believe my friend Steve may have started a bit of a trend in a new type of journal.

This post is awesome. So happy to have started following your work! Keep them coming. Our world needs better marketing rooted in deep thinking, and you are laying some excellent bones down to build a better skeleton!

Thanks for sharing!

https://instagram.com/monkmanual?igshid=YmMyMTA2M2Y=