How fast became normal: part 4

Benjamin Franklin and the cultural myth of "time is money"

Welcome back to another riveting installment of Dissertation Tuesdays. Today we’re talking about the US cultural myth of “time is money”. And that’s right. It’s in quotations.

Have you ever noticed the way we talk about time in US culture?

You’re wasting my time.

This gadget will save you hours.

I don’t have the time to give you.

How do you spend your time these days?

That flat tire cost me an hour.

I’ve invested a lot of time in her.

I don’t have enough time to spare for that.

You’re running out of time.

You need to budget your time.

Put aside some time for ping pong.

Is that worth your while?

Do you have much time left?

He’s living on borrowed time.

You don’t use your time profitably.

I lost a lot of time when I got sick.

Thank you for your time”

(source: Lakoff and Johnson, Metaphors We Live By)

We treat time as a resource to be wisely spent, invested for future return, or otherwise wasted. Our everyday language reflects that belief. “Time is money” has become entirely normalized in our culture, so much so that even questioning if that belief is unnatural — i.e., that it is socially constructed — may seem a bit odd.

My friends, I’m here to argue that “time is money” is indeed a belief shaped by our culture. And that, while the belief that time is a valuable resource does have some merit, it can also make us entirely miserable when left unchecked.

There are cultures all around the world who possess and practice a different orientation toward time. In general, Western cultures tend to possess a linear view of time (also known as monochronic), while many Eastern cultures possess a circular view of time (polychronic). There’s more nuance to the dichotomy, but I bring that up to illustrate that there is not a single orientation towards time that exists in this world. [I made a tiktok about that concept here.]

But I’m getting a little ahead of the main point.

So far, this series has discussed 1) how consumer culture is fast and how this speed has a negative impact on multiple stakeholders, 2) the theory of social acceleration and how our modern society is propelled forward by the interconnecting motors of the economy, social change, and pace of everyday life, and 3) a brief history of time in the modern economy and how enlightenment thinkers valued time spent working (and thus time consuming) over leisure time, ultimately deciding our society’s orientation towards a culture of mass consumption.

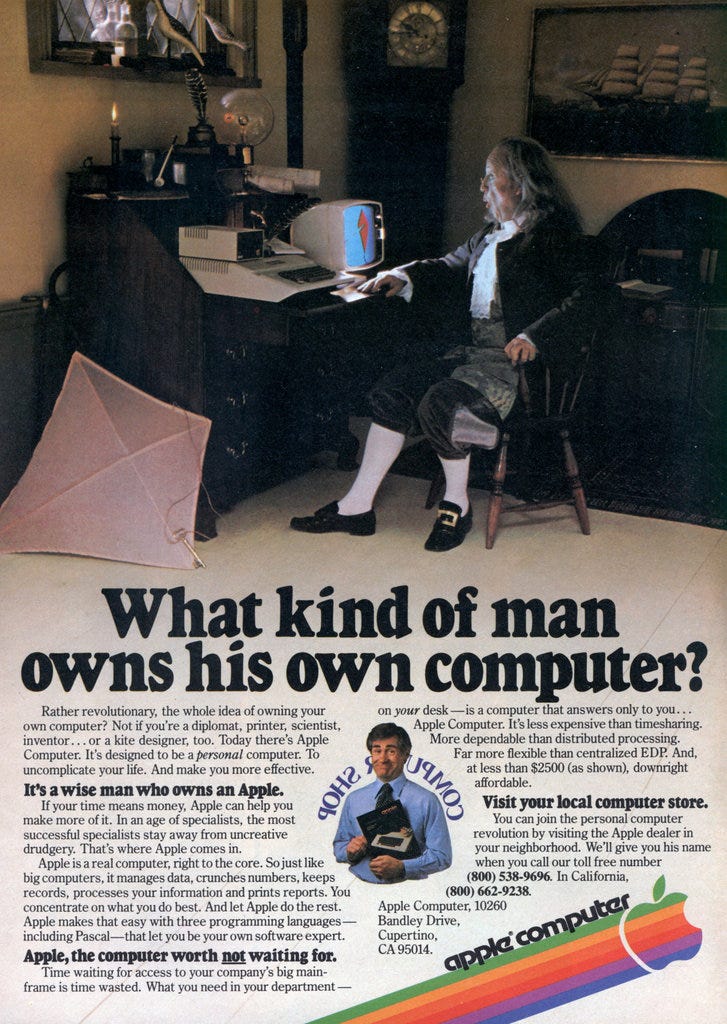

Now, in this post, we get to talk about Benjamin Franklin and semiotics. And I promise this will all tie together.

Benjamin Franklin and the cultural myth that “time is money”

Most people know Benjamin Franklin as our polymath Founding Father: an inventor, a statesman, a writer. He was also entirely influential to the early economic spirit and philosophy of the United States. Franklin wrote several pamphlets to disseminate his ideas, one of which was The American Instructor (published in 1748) which included a short article entitled “Advice to a Young Tradesman”. In it, he wrote:

Remember that TIME is Money. He that can earn Ten Shillings a Day by his Labour, and goes abroad, or sits idle one half of that Day, tho’ he spends but Sixpence during his Diversion or Idleness, ought not to reckon That the only Expence; he has really spent or rather thrown away Five Shillings besides. Remember that CREDIT is Money. If a Man lets his Money lie in my Hands after it is due, he gives me the Interest, or so much as I can make of it during that Time. This amounts to a considerable Sum where a Man has good and large Credit, and makes good Use of it.

Franklin is getting at the now-commonly accepted economic concept of “opportunity cost”: that there are necessary tradeoffs in our daily decision making and that a choice to pursue one option inherently means that we’re not choosing another, and that the “cost” of the unchosen option should weigh in our decision calculus.

By reminding his (mostly young, mostly male) colonial readers that there was a price on time; Franklin naturalized a linear cultural view toward time - that time was a finite, objective resource.

Benjamin Franklin lived his life by the principle that time was a resource. In his autobiography, Benjamin Franklin purported a certain use of time as “good”, “virtuous”, and “useful”. He emphasized the virtues of frugality and industry. Franklin vowed to “make no expense but to do good to others or yourself; i.e., waste nothing”. His self-instruction was to “lose no time; be always employ’d in something useful; cut off all unnecessary actions”.

Franklin believed that by striving for a set of virtues, a set of moral standards, he could be a good and useful citizen. And he was not shy to share his daily practices of time management and self-regulation (referred to as “a plan for attaining moral perfection”). Franklin set a cultural standard for successful living.

As Benjamin Franklin became mythologized in the culture of the United States, so too did his* quip that “time is money”. (*It is likely that the “time is money” proverb did not originate with Franklin, but he is credited with writing down and publishing the saying.)

The impact of such a strongly held cultural belief cannot be overlooked. As the "time is money” sentiment became repeated over and over again in common language, referenced to in popular culture, and transcribed in history books, the idea itself became immortalized. Untouchable. Unquestionable.

“Time is money” is now a guiding ideology, a cultural myth that permeates every aspect of US American culture.

However, our understanding of time is a result of historical construction: “just as our idea of history is based on that of time, so time as we conceive it is a consequence of our history” (Whitrow, 1988, Time in History).

Cultural myths and semiotics

The theory of cultural myths and the methodology of semiotics help explain how “time is money” became an enduring belief (i.e., a cultural myth) that both reflects and actively shapes US American culture.

My research draws on Roland Barthes’ Mythologies to show how print advertisements in the 20th century worked to constitute an inspirational and instructive guide-to-life for the American consumer — a set of social norms worth replicating.

(Editorial note: I tend to use the terms cultural myths / social norms / enduring beliefs interchangeably. The most simple definition of a cultural myth is this: a symbolic story that is repeated so often that nobody questions its origins, its truth, its motivation, or its consequences.)

Here’s why cultural myths are important to understand:

Cultural myths are sense-making devices that provide a lens of interpretation for the world around us.

Cultural myths provide a sense of shared cultural meaning for all within a society to draw upon.

Cultural myths seek to maintain a sense of social structure by stabilizing shared beliefs in a manner that can be passed down from generation to generation.

The theory of cultural myth is based on semiology. Semiology is a social science discipline that extends the laws of structural linguistics to other sign systems. A semiological perspective asserts that within any form of communication (from everyday interpersonal communication to the corporate design of commercial retail environments), a process of sign exchange and interpretation of sign meaning occurs. In this, semiology takes in any system of signs — images, gestures, musical sounds, objects, etc. — to create systems of shared meaning in society.

Ok pause. I get it - semiology, semiotics, sign meanings, etc etc… these all sound like weird words but I promise that you inherently understand what I’m talking about.

Let me briefly illustrate. In semiotics, a signifier (an object, or a carrier of meaning) acted upon a signified (a cognitive concept, or meaning itself) to form a sign:

The sign meaning is the denoted meaning. Denotation indicates a direct, literal meaning that an object may carry. Connotation, on the other hand, is a higher-order, constructed meaning. Denotation is simple and straightforward; connotation is a more complex structure, a product of human experience relying upon context and societal influence. The existence of connotative meaning reveals that meaning is a social construction, rather than a product of nature.

When this process happens over and over, and the same connotative meanings repeatedly arise from the same signifier, you get a cultural myth.

Through symbolic repetition and cultural preservation, cultural myths form our guiding cultural ideologies and beliefs. As Roland Barthes said, cultural myths are “certain to participate in the making of the world.”

The theory of cultural myth was developed to serve as both a political and cultural critique. Barthes believed that in order to create meaningful social change, you had to 1) be aware of cultural myths, and 2) interrogate them.

And I believe that “time is money” — the belief that time is a resource to be managed and optimized above all else — is 1) worth being aware of, and 2) worth questioning.

And if we question the myth of “time is money”, we may get closer to answering “how fast became normal”.

—

Next week in this series: how to conduct visual analysis to interrogate a “cultural myth”. This little tutorial may come in handy as you navigate the 10000s of subtle advertising messages we encounter weekly.

On Thursday: More on the idea that “Everything Communicates” - which is true in almost all aspects of life.