If you’re just jumping in, be sure not to miss Everything Communicates, Part 1 and Part 2.

In the mid-1990s, marketing sociologist Clotaire Rapaille swore up and down that Jeep Wrangler sales in the US faced a slump because the brand fundamentally lost sight of what their product meant to the American public. It was a new era of luxury SUVs and family lifestyle vehicles - vehicles that navigated suburban commercial-scapes and soccer complexes more than they crawled rocky trails and dirt paths. The SUV market began incorporating more interior comforts for passengers to enjoy on cross-town treks: plush seating, heated steering wheels, electronic windows, and lots and lots of cupholders (a very American thing, it turns out).

With eyes on the competition, the Jeep Wrangler team followed suit, incorporating more and more luxury upgrades into the vehicle’s otherwise straightforward design. But none of that would work for Jeep. The Wrangler continued to lose market share. Traditional market research methods (like surveys and focus groups) did not reveal a glaring error in the vehicle design. But Clotaire Rapaille, through his deep ethnographic research and “third hour” interview stories did. The headlights (at the time) were square; they should be round. Rapaille determined that, to the American public, a Jeep was a horse, signifying freedom and exploration. And if the headlights were its eyes, they should be round, as horses, definitively, do not have square eyes.

Jeep Wrangler changed the headlight design from square to round in 1996. America had their horse back. Wrangler regained marketshare. Coincidence or marketing genius? That’s for you to decide.

Clotaire would argue that Jeep is a successful brand because it plays into the US cultural myth of the cowboy: rugged and individual and tough and free and unbound by obligation. And even though the cowboy myth isn’t particularly true to the documented reality of the cowboy — most cultural myths distort history to make a story seem more appealing — the myth resonates because it is a familiar message that we’ve seen repeated over and over in popular media and folklore.

How cultural myths show up in marketing

As we’ve previously discussed, cultural myths are sense-making stories. They help us understand how we should act and interact with others. Increasingly, cultural myths also inform what we should purchase.

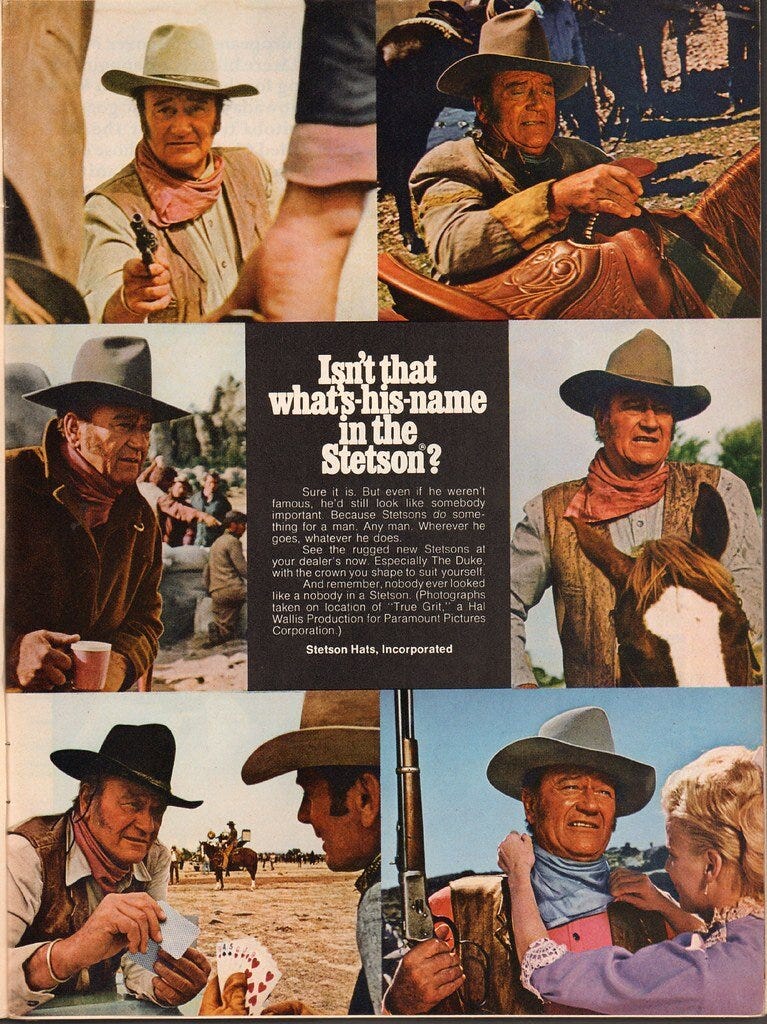

And it goes beyond the obvious, like the cowboy myth used to sell Stetson Hats.

Marketers are savvy when it comes to cultural myths. There is power in making an offering — whether a product, service, or an idea — more culturally relevant. (Since consumers live and breathe in a given culture, a more culturally-relevant offering just seems to “fit” better with a potential customer’s emotional and social preferences.) In fact, there is an entire specialization of marketers who engage in cultural strategy and they’ve revolutionized brands such as Volkswagen, Budweiser, Pepsi, and Jack Daniels.

Marketers practicing cultural strategy will intentionally embed meanings into marketplace offerings that resonate with the myths of a culture. This makes their offering seem more desirable, while simultaneously cementing certain ideas about what’s normal or what’s desirable into culture.

Let’s see how this works by returning to the cultural myth of the American cowboy— of rugged individualism as a path to freedom.

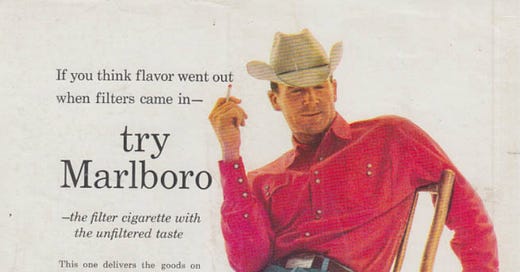

First there’s the obvious: the Marlboro man; Jack Daniel’s.

The cowboy myth also appears in the less obvious, like an advertisement for Diet Coke (“because I can”) or Levi’s jeans (“I will not sit at home collecting dust”).

The thing to note is that these advertisements latch onto stories and meanings that 1) already exist, and 2) are already championed in popular culture. Marketers are not creating new myths per se, but they are (as one academic put it), acting as ‘ideological parasites’, extracting meaning and riding on the coattails of existing cultural myths.

Sometimes a brand will strategically challenge a cultural myth, ramming its head against "just the way things are". In doing so, the brand leaves a distinctive mark with consumers and builds brand differentiation - a key part of brand strategy.

At this point, you may be asking: “Why does it matter what a bunch of advertisements say? Especially when we savvy consumers know to block them out?”

Fair point. My response is two-fold.

First, are you really blocking everything out? So much of the way we interact with the world today is market-mediated. The objects or experiences or ideas we consume are exchanged for a price. (Whether that price is money or attention or something else entirely is a post for another day.) Estimates show we are exposed to nearly 60,000 advertising messages A WEEK.

And second, it’s not just what marketers are doing now that matters. It’s what has already happened, what ideas have already become normalized in our culture as a result of the past 100+ years of marketing history.

To get a little theoretical, marketing—advertising in particular—plays an important role in the sociology of knowledge in that it presents a way of construing and knowing the world around us.

Consumer culture acts as a sort of “social reality” that holds various beliefs about how society ought to work, and aids in our individual socialization into the norms of our culture. As individuals, we take these cultural norms and respond to them, often consuming things in the process. Perhaps we purchase the latest trends to help us ‘fit in’, or conversely, perhaps we purchase an item that distinguishes ourselves from the pack and includes us as a part of a unique subculture.

In this way, marketing serves as an instrument of meaning transfer between the culturally-constituted world and the consumption of consumer goods.

The culmination of everyone’s individual personalizations, and their sharing of those personalizations with others, shapes how culture moves forward. Consumer culture is dynamic and can change. However, forces like cultural myths work to keep things the same, consistent over time.

That is why, when consumer culture reflects a belief like “time is money” or “faster is better” or “you need to be energetic and outgoing” to be successful, it’s worth taking a closer look.

It’s worth interrogating the meanings of (seemingly quite innocent) marketing messages (that we seemingly do not notice).

—

Thank you all for being here. As always, I’d love to hear your thoughts. What cultural myths do you see at work in consumer culture? Which brand stories resonate with you (even if you can’t quite put your finger on it)?

Not a Consumer will be on break next week and will return March 7th with a look at our first theme of “time is money”. See you then!

"It’s worth interrogating the meanings of (seemingly quite innocent) marketing messages (that we seemingly do not notice)."

PREACH!!! :) "seemingly quite innocent" and "seemingly do not notice" equates to fertile ground for insidious impact.

Thank you for the fascinating work you are doing!