I had never seen a chicken truck until moving to Northwest Arkansas1 ten years ago.

Commuting down highway 412 was a daily practice in dodging white feathers hitting the windshield and also the large eighteen-wheelers carrying the birds from which the feathers flew. If, by unfortunate circumstance, the traffic pattern forced you to drive behind a chicken truck for any length of time, you’d disassociate by turning up the radio and avoiding eye contact with the birds AT ALL COSTS. And heaven forbid at this very moment you might recall passages from Upton Sinclair’s The Jungle or any part of that one PETA-sponsored documentary you saw in middle school.

Long bike rides on the weekend weren’t much better, zipping past large industrial chicken coops that once housed the chicken truck birds. Climbing a hill, you’d be met with a pungent mixture of ammonia and other gas wafting from the habitat, never quite clearing, stuck in the muddiness of Arkansas humidity. Thirsty for air, it was always a game time decision as to whether breathing through your nose or breathing through your mouth would be the wiser choice. Sometimes, it was decided, better to not breathe at all, an exercise in VO2 max.

These irritants were small, distant. They didn’t mean much. But I think about them often now that we have backyard chickens.

Hi there! all-consuming is switching to a summer posting schedule: once a week on Tuesdays, alternating between the “twenty shades of time is money” series and miscellaneous topics related to conscious consumerism— like today’s post. A little pool-side reading, perhaps?

Last year, after watching hundreds of hours of homestead youtube videos, my husband wore me down to the idea of backyard chickens. I wasn’t necessarily against it, but it also... was not my thing. Anecdotally, when you talk to chicken couples, there’s always one person who is more into it than the other, but rarely do the birds fail to win over the heart of the holdout.

Pregnant, I was not interested in raising baby chicks on top of caring for a newborn. Thankfully, we had friends with an excess of adult birds who offered to share some of their older hens with us, to help us get our chicken-footing. My husband and I thoroughly discussed the responsibility of labor associated with caring for the chickens, he built a chicken coop, and a couple weeks before welcoming our second son, we welcomed six hens.

A year later, my affection for the birds has inched to north of neutral. I would hesitate to say that I love the chickens, like big emotion type love, but I do have affection for the species in an entirely new way.

Coincidentally, these feelings have been bolstered not only by personal experience with the birds, but also by learning more about their role in history and our modern food system. So when I read Anne Helen Peterson’s interview with Tove Danovich behind the popular instagram account best little hen house and author of Under the Henfluence, I knew I had to dive in. (Funnily, my husband gifted me the book. He really wants me to like the chickens.)

There are so many excellent parts of Under the Henfluence, particularly the brief ethnography outlining a trip to Murray McMurray, the foremost supplier of backyard chickens in the U.S. (if you have the book, chapter 2). I was struck by, how even in a system that is entirely more ethical than its industrialized counter-part, there are still hard facts to reckon with. (The disposal of most male chicks, because they won’t grow up to lay eggs, for example.)

And as a marketer reading about the phenom of backyard chickens, historically a normality and now a symbolic trend, I’m reminded that everything can be marketing, and everything can be marketed… yes, even chickens.

Whether spurred on by supply chain issues stemming from the pandemic, inflated egg prices, or a desire to embrace more sustainable and ethical food sources, backyard chickens have experienced a boom. Exact stats are hard to come by, but activity on instagram and TikTok show how bird keeping has regained a place in the cultural consciousness.

Again, as a marketer, I see a trend: an activity romanticized by a generation (mine), to which a previous generation may scoff. When I told my grandmother, who grew up in poverty— a context which for her family necessitated briefly living in an abandoned chicken coop— that I was electively tending to backyard chickens… well, she didn’t have much to say. The silence communicated, “why would you choose to have chickens, when you can afford to buy eggs from the store?”

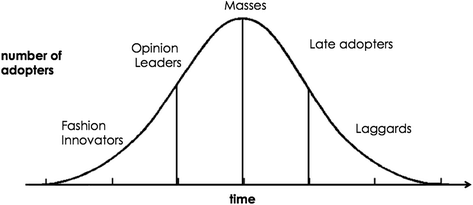

Of course, trends are context-dependent. Just because the Brooklyn (or Fayetteville, Arkansas) set flocks (ha) to chicken-keeping doesn’t mean it’s a universal trend. But that’s also how trends work; they sort of live within particular subcultures. Very few trends are truly mass market.

As consumers, we expect to see trends in categories like fashion, home decor, food and beverages, and even pet dog breeds… but the trend-ification of specific backyard chicken breeds (again, as outlined in Danovich’s work) was a surprise. Some chicken breeds are chosen purely for the color of eggs they produce (do you, the consumer, prefer robin-egg blue or a mellowy-tan?). Others are chosen for their regal comb or feathery crown. Catalogs display the choices, like different colors of a shirt.

And because of social media’s recent influence on breed preferences, hatcheries like Murray McMurray struggle to perfect the balance of supply and demand for certain breeds of chicks. Some they overproduce, breeding too many chicks that consumers do not want, and some they underproduce, failing to meet consumer expectations of availability. Mismatched supply doesn’t matter as much when we’re talking about inanimate products… but with recently-hatched chicks that must be sent out to customers within a 24-hour time period, an imperfect estimation of supply and demand leads to… (how do you put this politely?) waste. Put unpolitely, a trashcan of dead chicks.

I wasn’t planning on the above paragraph, rant-like in nature, because I don’t have a solution to propose and I don’t like to just poke out problems. But man oh man do I have to grapple with the fact that there are consequences associated with— what for my family is merely— a charming past time activity.

A theme apparent in Under the Henfluence is that there is no perfect system; and that a triumph of the backyard chicken movement is its ability to bring humans closer to an animal that has experienced extreme commodification through industrial agriculture. (Just think of the way chickens and eggs are promoted as bland, versatile, cheap pantry-staples.)

Sustainability is never about perfection. Progress is never about perfection. And the backyard chicken movement is a perfect example of this.

Why this location matters: home to Tyson foods, largest processor and distributor of ‘ready-to-cook’ chicken in the U.S.

Lovely read. After hearing chicken-rearing stories from my father’s experience in the 1940s, the task seems less than desirable. Thanks to your husband’s tenacity, your children’s egg knowledge is vast, much like my own father! As for marketing, there’s a chicken place in Seattle named Bok A Bok!

Dear Sarah, so appreciate your perspective on all things around brand, trends and consumption. As one who likes to admire others backyard chickens (our place out on the North Fork of Long Island NY has a number of folks who have backyard chickens) I'm fine with admiring them as I do others' pets. Cute, though, no thanks to come live in my backyard. On the pet front, I got worn down with having cats a number of years ago. I was definitely the hold out in my family. After 15+ years, along with a variety of cats that have come and moved on (as in the rainbow bridge journey) I've come to accept the creatures as enhancing my life (aside from the litter box scooping and the occasional fur-ball gift.. ) Keep writing!!