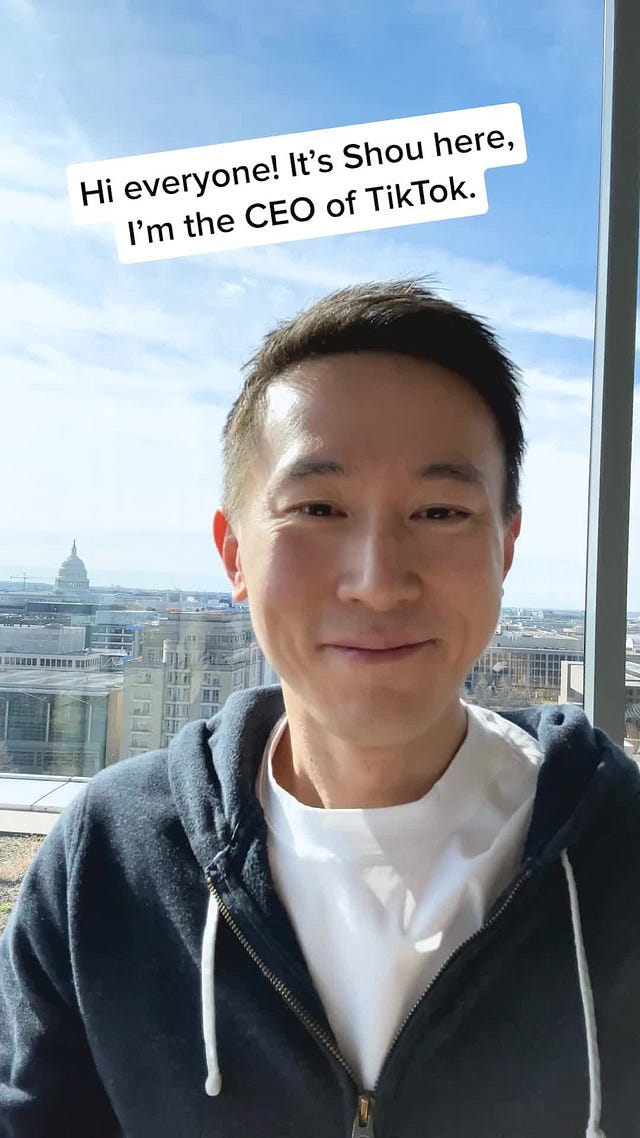

A couple days ago, I opened TikTok1 to see the following video from company CEO, Shou Chew:

If you spend any amount of time on the addictive app, you know it’s a bit odd to receive video messages on the platform directly from the brand itself. In fact, I think it was my first time seeing such a message. I watched the video twice, rolling its meaning (and motivation) around in my head. Remember, everything communicates. And this was no exception.

An hour after this post is published, Shou Chew will testify before Congress regarding tiktok’s continuance in the US.

There’s already been a lot written about a potential tiktok ban, from its implications for free speech and first amendment rights, to what a tiktok ban could mean for national security and foreign relations. So I won’t explicitly discuss those topics. I’m also not going to discuss the (in my eyes, legitimate) theories regarding Zuckerberg’s role in a PR campaign against the brand.

My knowledge and expertise is in marketing, specifically brand strategy, so I’m going to stay in my lane here and discuss specifically what the tiktok brand means to US Americans, and why that’s important.

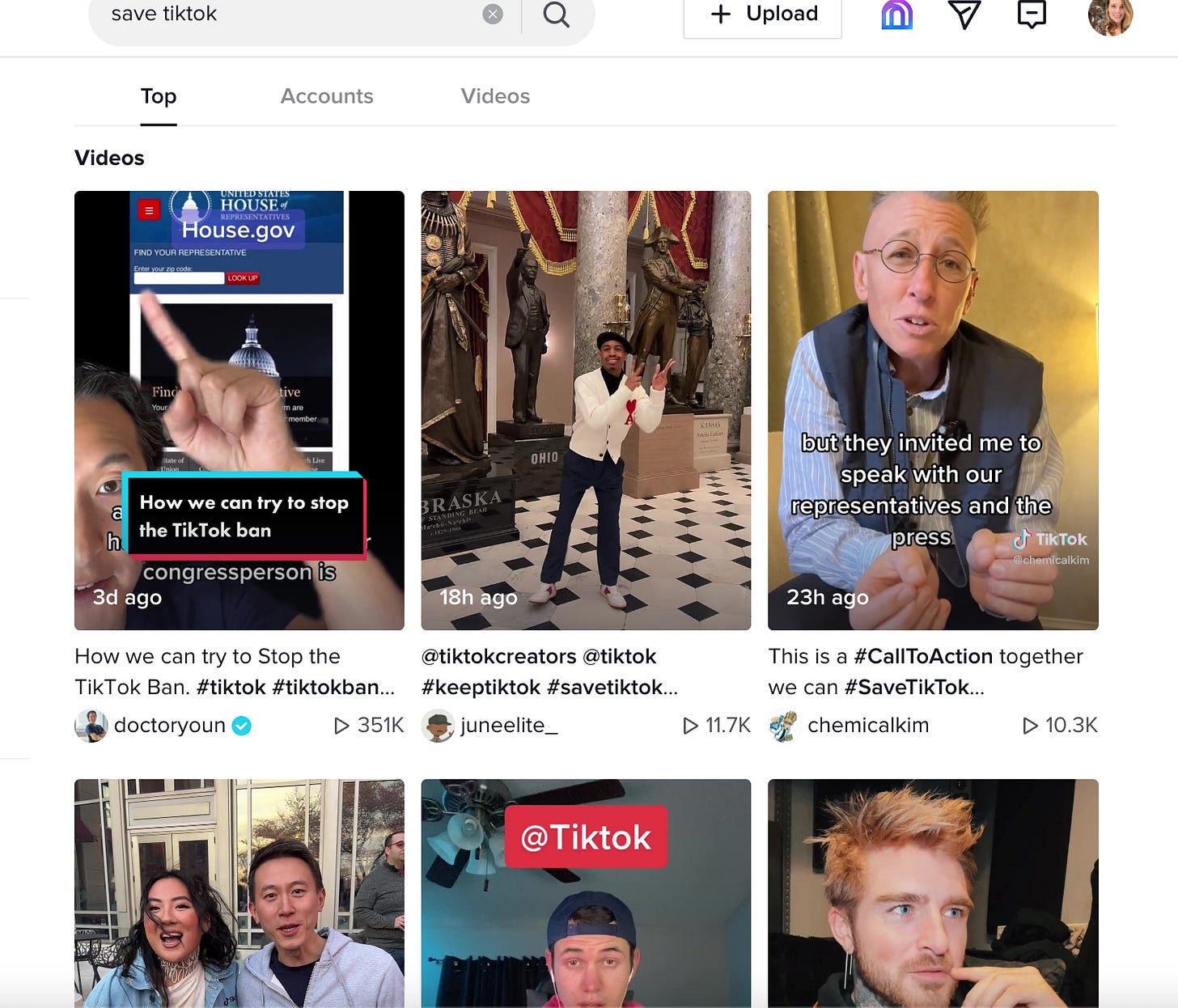

My first thought watching Chew’s video (above) was something to the extent of: “Ahhh. That’s really smart.” Of course, there are 150M registered US Americans on tiktok2, and to quote David Guetta, it’s a force field. Stroke the energy of your users ahead of a week-long congressional debate and let them act as a seemingly invisible barrier of strength, fighting on behalf of your survival…? It’s a smart preservation strategy.

A quick scroll of the top comments to Chew’s video show the range of earnest support and caring concern from top creators on the app:

Additionally, tiktok mobilized content creators to Washington D.C. this week to speak with representatives and the press, in hopes of highlighting the platform’s more positive features:

The second thing that stood out to me about Chew’s video was the bit about how many US small and medium-sized businesses use tiktok to connect with customers. This is true. You’ve heard of “tiktok made me buy it” and the success of Scrub Daddy and #BookTok and niche product companies selling out of stock because they went viral. Using ‘small business’ as a reason to maintain tiktok as a democratic marketing platform is totally compelling to both sides of the aisle.

My third thought in response to Chew’s video came after he shared tiktok’s brand mission to “inspire creativity and bring joy”. Having used the platform for nearly 2 years, I honestly had no idea what tiktok’s brand’s mission was on paper. (editorial note: a brand mission statement is a vital part of brand strategy, ideally serving as an existential umbrella — “a reason of being” — under which all other strategies operate.)

“Inspire creativity and bring joy.”

Hmm.

I think tiktok is (and does) much more than that.

Here’s the thing. A brand isn’t a thing just because they say they are a thing. Brands are meanings; amorphous as they may be. Brands are, on paper, intangible assets. Brands are the value received and felt by stakeholders above and beyond the measurable value they “should” be worth. And many times, a brand doesn’t control the cultural definition, or value, of itself.

The meaning of a brand is filled in by various actors who shape brand meanings by their perceptions and experiences of them. Cultural marketing strategist Douglas Holt identifies multiple authors of a brand's story3: the public (PR, media), customers (organic voices), influencers (a mix of the aforementioned two), and lastly… the brand itself.

A company can have a shiny mission statement, but if that mission statement doesn’t line up with the lived experience of the brand, then, well, it doesn’t mean anything. It’s literally… just words on a screen.

So let’s think about this in the context of tiktok.

Some people know tiktok as an app that instructs middle-schoolers to destroy bathrooms; other people know it as a source of on-the ground investigation of events uncovered by mainstream media; others as a true crime spectacle; others as a platform of clothing and makeup hauls and gross overconsumption; others as dopamine-enhancing dance challenges; others as dinner inspiration; others as parenting advice; and others as a haven of mental health support.

Tiktok has a hundred-thousand (or more) meanings. Which is why I believe tiktok is the most difficult brand to manage in the United States, or maybe even in the entire world. How do you manage a brand that simultaneously means something so different to so many different micro-communities? (While still operating under the larger brand mission to “inspire creativity and bring joy”?)

In brand strategy circles, you’ll hear it said that ‘strong strategy is about knowing when to say no, and knowing who your customer is… and isn’t’. This doesn’t apply to tiktok, because tiktok is literally for everybody… but not everybody all at once all the time and everywhere (that last sentence could almost be an Oscar-winner). Tiktok’s strength lies in its ability to form super-hyper-focused segments of subcultural communities through it’s super secret and super effective algorithm.

You’ll also hear it said that ‘strong brands are about community’. Tiktok has not taken that advice to imply it needed to be a host for a single community, rather tiktok has become home to an uncountable amount of micro-communities. (Some marketing thought leaders might call them ‘tribes’.) And tiktok is really good about gathering tribe members together, without situating themselves as a leader of any given tribe, per se.

That’s why once the algorithm has figured out that you’re a 30-something-mom of two young children who had a short stint in academia and who also used to be a corporate ladder-climber but now stays home and writes about conscious consumerism in her spare time, you don’t see any content about middle school bathroom destruction. Instead, you see a mix of videos featuring practical Get-Ready-With-Me’s, sustainable living tips, executive presence coaching, gentle parenting advice, light social critique, national news, dopamine-inducing dance routines, tonight’s meal inspiration, and Kardashian satire. Tiktok shows me other people like me… most of the time.

Tiktok failed to load.

Tiktok failed to load.Enable 3rd party cookies or use another browser

Occasionally, I can sense tiktok stretching the bounds of my “normal”, as if to ensure they’ve saturated my sense of tribal belongingness. I’ll begin to see videos that offer a viewpoint or a glimpse into a world outside of my own, but not too far outside.

I view these moments as a practice in phenomenological inquiry: observing and seeking to understand someone else’s lived experience, so I can sharpen my own beliefs about the world. My interpretation and response lies on a spectrum of: “Yes, that perspective resonates, let me fold it into my set of operating beliefs” to “No, that doesn’t quite sit right with me, for x-y-zed reasons, let me solidify my stance there” and also includes the middle-ground, “Hmm… perhaps there is something new to learn here, worthy of further pursuit”.

Such inquiry requires active, rather than passive consumption of tiktok. Much of today’s media literacy involves 1) consciously discerning what to pay attention to, and 2) what to do with new information, if anything. (Yes — there is such a thing as conscious media consumption.)

Some questions running in my mind when consuming tiktok include:

Do I take this content as truth? Do I find it intriguing? Do I roll my eyes and scroll on? Do I become angry and tempted into a keyboards debate? Do I cry? Do I doubt the life I’m living? Am I better person for having consumed that content? What have I learned? What have I gained? What have I lost? Is this tribe for me?

And one last question:

Does tiktok deliver on their brand mission to inspire creativity and bring me joy? Yes, but it also does much more than that to shape my subjectivity — for better, or for worse. Tiktok isn’t just managing a brand. In a way, it’s managing the making of me.

—

Every Thursday I post a short, low-edited thought about consumer culture and/or conscious consumerism. These are just conversation starters - scratching at the surface of a deeper thing that I’m still discovering. Would love to hear your reactions, thoughts, questions, etc. below!

I don’t care to capitalize both T’s in TikTok every time I write out the brand name; will be using ‘tiktok’ throughout.

This is the first time TikTok has been so forthcoming with the number of registered users. Since they don’t legally have to report numbers (privately traded), they have always been coy about the number of registered users in the US - estimates hovered closer to 100M.

I’m adapting Holt’s model slightly for 2023 to account for the blur between social media influencers and popular culture. Holt’s original 4 brand story authors are “The Firm”, “Influencers”, “Customers”, and “Popular Culture”.

Thank you Skyler! Home life has been a little robust so I “took some time” - will be back next week!

I hope you're well, Sarah! I've missed this week's dive into industrialized advertising psychology. Looking forward to the next!