How Fast Became Normal: Part 1

Exploring temporal rhetoric in US consumer culture

Every Tuesday I post a short excerpt from my dissertation which explores the phenomenon of social acceleration and consumer culture.

If you missed last week’s introduction post on substack, you can read that here.

Consumer culture is fast. Goods, services, people, ideas, and values – the material and nonmaterial aspects of culture – are moving more quickly throughout our economic system than ever before. Such acceleration affects diverse stakeholders including people, public, and planet.

Many industries and facets of everyday life illustrate this phenomenon, but perhaps some of the most telling are the categorical examples of fashion, food, and travel.

Fast fashion refers to a dominant fashion system driven by speed, one that encourages frequent turnover of trends and planned obsolescence. Fast fashion retailers around the globe such as Forever 21, Primark, Zara, and Shein quickly bring new styles to consumers, at ever condensed prices, while demanding increasing speed throughout supply chains. Consumers, for fear of missing out on the “new” and the “what’s next” in the context of their identity management projects, are eager to comply with a hastened pace of purchase: the average American purchases 68 new pieces of clothing a year, roughly 1.3 garments every week; in contrast, the average American owned just 9 outfits in the 1930s. At the same time, the relative price for clothing has continuously fallen. In fashion, cheaper and faster reigns.

Food that is fast has become nearly synonymous with a busy lifestyle. The hallmark of fast food is that it is convenient and it saves time, a tempting appeal to time-strapped consumers. And while “fast food” may conjure visions of golden arches and southern colonels, foods that are fast aren’t always delivered at a pickup window or restaurant counter. Packaged and processed foods found on grocery store shelves also offer the time-saving and convenience benefits that attract consumers to certain food choices. “Fast foods” are foods that can be accessed easily and quickly, come prepared, can be eaten rapidly, and are absorbed quickly into the bloodstream. As a tradeoff for choosing fast food, consumers are able to budget less time spent cooking and building culinary skills. Approximately 55% of the calories in a standard American diet now come from processed convenience and fast foods. And similar to fast fashion, the structural conditions that allow the rapid movement of food throughout the marketing system have also made food cheaper and more accessible, even if sacrificing quality.

Even travel, once an endeavor that delivered a seeming respite from time (as illustrated in the below Japan Airlines advert from 1962), has experienced a startling change as a result of society’s dominant temporal logic. Advancements in technology and modern transportation have allowed goods and people to travel greater distances in shorter amounts of time. The rate at which travel occurs has also hastened.

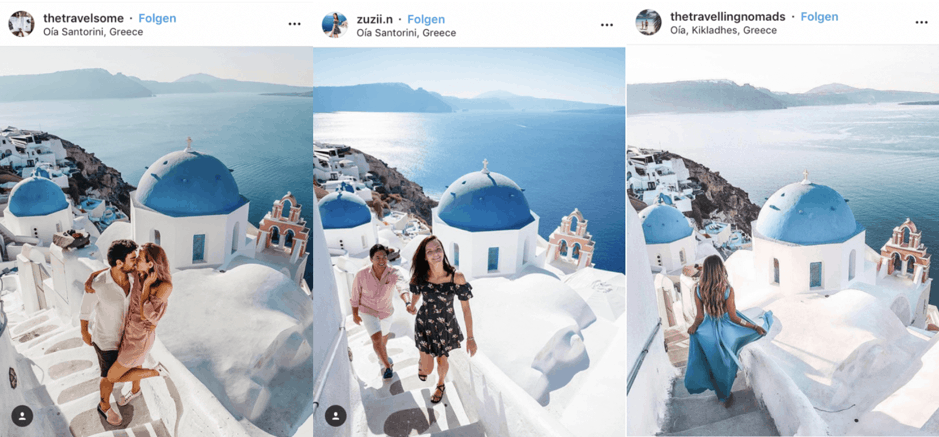

“Fast travel” is often preoccupied with reaching a destination, evoking a logic of means-end rationality, and “involves intensive energy consumption”. Corporate executives bounce from continent-to-continent and city-to-city negotiating and finalizing complex agreements of capital in face-to-face meetings, which are preferred over virtual meetings (Editorial note: this trend has since been tempered in the wake of Covid-19, with business travel not expecting a full rebound until 2026). Leisure travelers, lured by instagram geotags and budget airfares, are eager to visit and share via social media jaunts to popular tourist spots around the globe before jet-setting to another site.

The acceleration seen in the fashion, food, and travel industries is similarly reflected throughout many other industries and aspects of life. In short, fast has become normal. Modern society and consumer culture continue to move at an ever-hastened pace; the world we live in is accelerating. And as aspects of everyday life continue to tumble down this trajectory, physical and social constraints begin to give way.

For fast fashion, this reality was most clearly revealed in the spring of 2013 after the tragic collapse of the Rana Plaza factory outside the major capital city of Dhaka in Bangladesh. Over 2500 garment factory workers were swept in a mountain of smoke and debris as the structure of the building gave way. After three weeks of search, 1100 workers were declared lost. Chillingly, the Rana Plaza factory primarily produced goods for leading fast fashion brands. Retailers and consumers in the developed West now had to reckon with the reality that for the sake of fashion, lives had been tragically lost; the ever-quickening patterns of production and consumption proved deadly for key stakeholders within the marketing system.

Fast and convenience food also yields grave consequences, not only for end-consumers of the product, but also to the publics which they belong. Largely devoid of nutritional density and calorie efficiency, fast food consists of highly processed substances including excess meat, salt, and sugar – all of which have been linked to health risks such as obesity, diabetes, heart attacks, strokes, dementia, and cancer. A public health crisis arises from the popularity and accessibility of fast food as over 100 million Americans face obesity and 37 million face nutritional deficiency, aggravating mental and physical wellbeing for individuals and communities.

Meanwhile, fast patterns of travel highlight another social issue entirely: degradation of planet and culture. Business travel is responsible for nearly half of a given company’s total carbon emissions, contributing to changes in climate and increased levels of pollution. On the tourism side, popular destinations such as Machu Pichu, Venice, and Iceland experience an influx of travelers, growing in ever greater numbers by the year. “Overtourism” has been coined to describe accelerating amounts of travel that affect the planet in terms of pollution and overcrowding at natural and cultural sites. This increase in travel intertwines issues of ecology, economics, and culture.

As each of these industries illustrate, the speed of our modern society – and of our consumer culture – can result in negative externalities for people, public, and planet. Enormous consequences for consumer wellbeing and social systems stem from the relentless pursuit of acceleration throughout the marketing system. And as the dance between marketing production and consumer demand increases in tempo every business quarter, such consequences can be expected to continue.

Social scientists are increasingly interested in the effects of ever-increasing speeds (e.g. Hassan 2009; Rosa 2013). Examining the phenomenon of social acceleration presents an opportunity to look inward. This essay does just that, interrogating our market-mediated relationship to time. This pursuit will answer the question: How did fast become “normal” in modern consumer culture? (And how does something become “normal” anyway?)

Next week we will continue by exploring ‘social acceleration’ and how a hastening temporality shows up in consumer culture…