Last week my husband, baby, and I took a much needed very warm and very sunny and very sandy vacation.

We found ourselves in Puerto Rico, mainly because it was one of the warmest places we could visit as US citizens without a passport. (Baby’s passport application is now in the mail - I hadn’t planned ahead for this winter escape.)

Puerto Rico is a US territory complete with Walmarts and Church’s Chickens and Burlington Coat Factories and Chuck E Cheese, so upon landing in San Juan you might perceive the island as appearing prototypically “American” — yet that would be a misreading, as Puerto Rico is a place very unique from the mainland and has a culture completely its own.

I like to make a game of noticing the similarities and differences of places I travel, constantly comparing to my baseline understanding of “home” (in cozy midwestern USA).

If you’ve traveled throughout the US, you know that New Orleans is different from Chicago is different from Seattle and St. Louis is different from Minneapolis and Greenville, South Carolina.

Honestly, cultural differences are easier to notice. Structural anthropologist Claude Levi-Strauss discussed this in his concept of binary oppositions, wherein meaning comes from the difference between two things; thing A is that thing partly because it is not thing B.

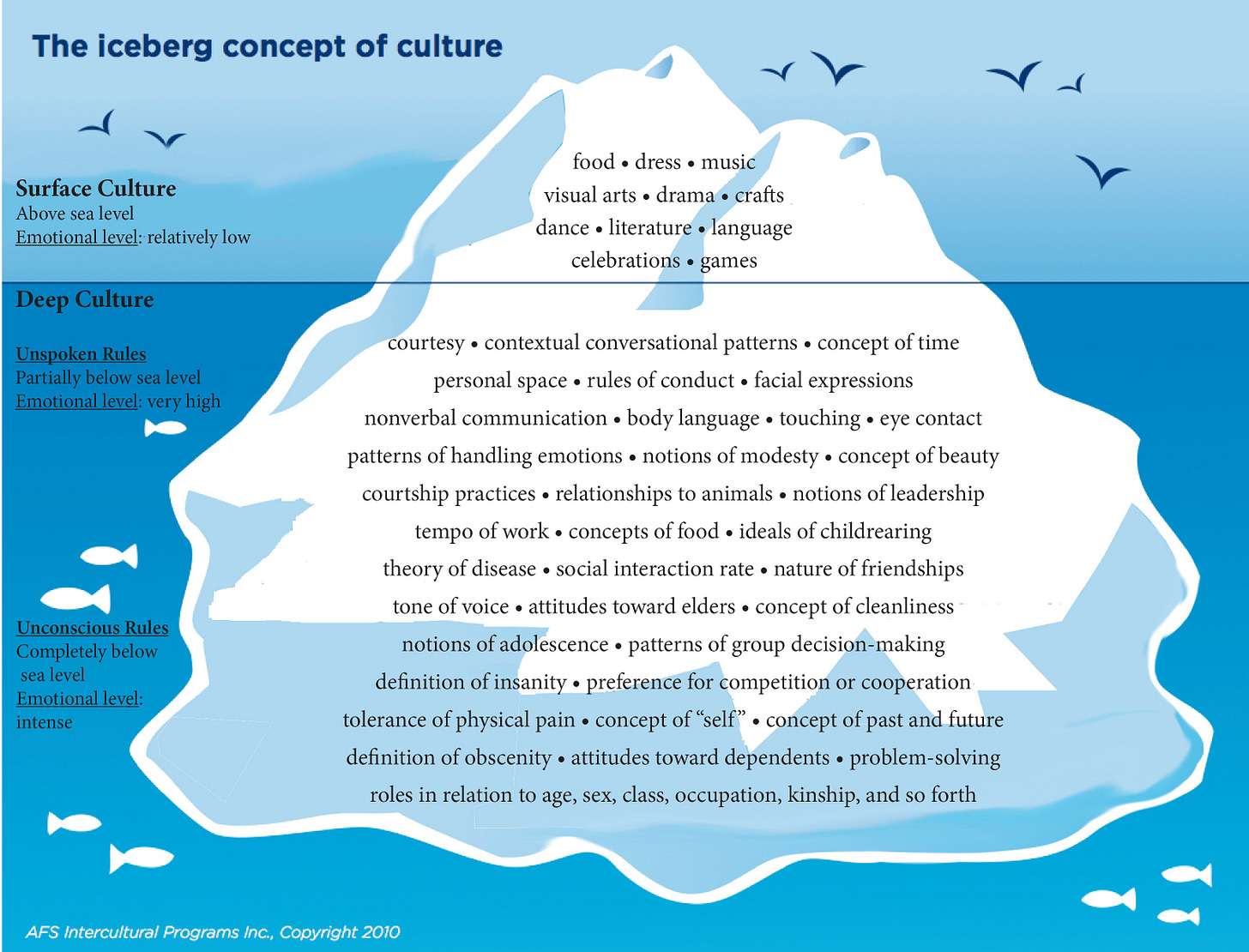

In a place as diverse as the United States of America (and its territories), differences are easy to spot: accents, affinity for sports teams, favored grocers (HEB or Hyvee?) This is surface culture.

The similarities are quieter. The guiding values and institutionally-governed norms. This is the deep culture.

Given that, I acknowledge the risks in making any sweeping statement about the whole of US American culture.

However, this series is going to do it anyway. The findings presented over the next 20 weeks derive from research analyzing nationally-ran print advertising messages throughout the 20th century, a formative era for US culture and commerce.

The uniform nature of print advertising in the 1900s was in spite of regional differences that surely did exist - undifferentiated mass communication was simply the M.O. of the time. (Today’s marketers have the benefit of some pretty sophisticated abilities to segment and target audiences by micro-geographies.) And while it would be fair to question whether such uniform advertising messages were received and applied entirely the same across the country, I also believe it is fair to say that certain ideas do govern (institutionally or more casually) over the whole of the United States. I believe that time is money is one of them.

Ok, enough caveated introduction for one post.

With that, I welcome you to the first of twenty shades of “time is money”, the cultural myth that orients our society and daily lives and begs to be exposed.

Theme #1: FAST IS AMERICAN.

“Fastness is patriotic, democratic, and American. We as a society benefit when we all go fast.”

Someone at Samsung already figured this out, and expertly embedded the insight into a 2017 commercial for the Galaxy Note7:

The Samsung advert is a hit because it simultaneously pokes fun at and compliments an aspect of US American culture, namely how fast/productive/success/efficiency driven we seem to be.

Turns out, advertisers have been tapping into this kernel of truth for over 100 years.

Here are a few images from my research that also represent the idea that a certain (ahem—fast) orientation towards time is quintessentially American.

Cultural myths aren’t entirely falsehoods. They’re always rooted in a kernel of truth, just a truth that’s been stretched for a certain purpose. I’m not here to argue that time is not a finite thing, or an objective thing, or that we only experience so much of it in a given day. But I am here to say that… maybe we should evaluate our culture’s normative beliefs about this concept that seems to govern so much of our lives and civility.

Roland Bathes remarked that cultural myths are “delusions to be exposed” - their meanings interrogated - and that is the aim of this research. By identifying the various way in which ‘time’ has been positioned as a resource to be used and spent and invested in a particular way in our culture (through the myth of “time is money”), we can better understand and question our own relationship to time.

And I’m interested to hear from you. How does “time is money” show up in your life? Specifically, how does the belief that “fastness is patriotic, democratic, and American” show up for you? Or does it not? I’m interested to hear that too.

Thanks for reading Not a Consumer.

For the next several Tuesdays, posts will explore the twenty shades of time is money as discovered in my dissertation research.

Thursday posts will continue with misc topics related to consumer culture and conscious consumerism.

The greatest form of flattery is if you’ll share this post with a friend who may be interested!

Perceptive