If you value what you measure; it seems our society values economic growth.

Reading headlines about the economy, the word ‘growth’ seems to signal a sigh of relief. And for the aggregate macroeconomic system, sure. But what about for the daily lives of individuals? Or the cohesiveness of our communities? Does the sum necessarily reflect the reality of the parts? Is economic growth… always good?

Welcome back to our series, twenty shades of “time is money”. Every Tuesday we’re breaking down findings from my research on social acceleration, marketing, and consumer culture.

This research helped me better understand my own relationship to time and consumption (and specifically, the felt need to constantly be busy and hurry through life and buy things as an antidote to this frenzy). Thank you for reading, and I hope there is a nugget of inspiration for you here too!

"Our economy requires fast and efficient consumption of inputs in order to quickly produce outputs; we're always driving for growth."

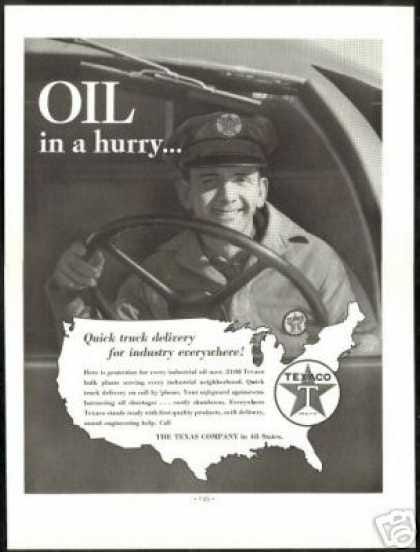

Twentieth century advertisements in the Economic theme position their value offering as something that can fuel economic endeavors:

The previous advertisements suggest that there will be financial growth/return if resources are invested wisely. The following advertisements specify a particular (hard) work ethic as a key input in our economic system.

The way we measure the success of our economy isn’t the same way we should measure the success of our lives.

Economic growth is typically captured by GDP (Gross Domestic Product), a sum of consumer spending, government spending, private investment, and net exports.

Over the past 70 years, much of US GDP growth has come from increased consumer spending (which includes things like clothing and groceries and haircuts and home furnishings)1. In fact, consumer spending now accounts for over 2/3 of US economic activity. Between the years 1948 and 1973, increases in consumer spending corresponded neatly with a rising standard of living across the US population. For this reason, economic growth is (rightfully, in that historical period) credited with making the lives of people generally better. However, consumer spending increases in the last 50 years reflect an increasing inequality of income.

In 1968, Bobby Kennedy waxed a poetic argument that beyond a certain level of material comfort for the masses, economic growth (at least, economic growth as measured by GDP, or its closely related cousin, GNP) did not automatically assume a ‘better life’:

“Even if we act to erase material poverty, there is another greater task, it is to confront the poverty of satisfaction - purpose and dignity - that afflicts us all.

Too much and for too long, we seemed to have surrendered personal excellence and community values in the mere accumulation of material things. Our Gross National Product […] - if we judge the United States of America by that - […] counts air pollution and cigarette advertising, and ambulances to clear our highways of carnage. It counts special locks for our doors and the jails for the people who break them. It counts the destruction of the redwood and the loss of our natural wonder in chaotic sprawl.

It counts napalm and counts nuclear warheads and armored cars for the police to fight the riots in our cities. It counts Whitman's rifle and Speck's knife, and the television programs which glorify violence in order to sell toys to our children.

Yet the gross national product does not allow for the health of our children, the quality of their education or the joy of their play. It does not include the beauty of our poetry or the strength of our marriages, the intelligence of our public debate or the integrity of our public officials. It measures neither our wit nor our courage, neither our wisdom nor our learning, neither our compassion nor our devotion to our country, it measures everything in short, except that which makes life worthwhile.”

The point being, economic growth does not always equate individual or collective well-being. For that, alternative measures like the Gross National Happiness (GNH) Index may do the trick:

Because we have an economic system that values growth, we also have a consumer culture that breeds discontent.

Growth requires continued spending. Our system is incentivized to promote increased inputs for increased outputs; increased consumer spending to bolster GDP; “out with the old and in with the new”. How does this materialize in consumer culture?

An introduction of discontent (through trends, comparisons, the deluge of “you need this newer, better thing!”)

Planned obsolescence (forcing your hand to buy something new when you didn’t necessarily need to or want to)

It’s how we got from buying fewer than 20 new items of clothing a year in the 60s to nearly 70 new items of clothing (on average) today. The implications of such growth in a single consumer category have reaching implications both for the environment (e.g., unnecessary extraction of resources, increased manufacturing and distribution pollution, premature end-of-life disposal and waste) and human welfare (e.g., unethical working conditions stemming from ever-shortening production deadlines).

As a consumer, we often just see what we see: new racks of clothing at Target, different than the ones we saw last month.

I’m a fan of lifecycle thinking because it elucidates the (often hidden) externalities associated with the production and consumption of material goods.

I’m also inspired by perspectives that push us to acknowledge the limitations of material growth while championing human ingenuity. Take, for example, Michael Mezz’s take on sustainable de-growth:

Even foundational marketing thinkers Philip Kotler and Sid Levy promoted de-marketing (50 years ago!), stating that “rather than blindly engineering increases in sales, the marketer's task is to shape demand to conform with long-run objectives.”

What are our long-run objectives as a society? Health? Happiness? Freedom? Sustainability, not only for the environment, but for our very lives?

How do we value these objectives? How do we assign them meaning?

The answers lie in what we choose to measure.

The ever-constant push for growth… in every aspect of life but especially those related to our personal contributions to the economy… is yet another way in which the cultural myth “time is money” shows up in our culture. In my research, I found 20 (!)

So many other writers seem to be digging into this topic currently. There is a cultural zeitgeist around reclaiming our relationship to both time and consumption, and I’m here for it.

Next Tuesday in this series, we’ll explore the idea that “if you earn (and spend) enough money, you can escape time.”

Consumer spending refers to the purchases of goods and services by households, such as clothing, food, and entertainment. These purchases are considered final goods or services, as they are consumed by the households themselves and are not used as inputs for further production.

I look forward to reading this every Tuesday! Keep 'em coming... Would be delighted to catch up again soon. Will send you a note soon ...